Nasty cartoons

From Paul Revere's propaganda cartoon of the Boston "Massacre" to the British press, 18th-century political cartoonists were vicious and often scatological. A family-rated Beetle Bailey cartoon precedes the 18th century venom that represent the era of After Yorktown.

Beetle Bailey, 2010. In popular myth, the Revolution ended with the Battle of Yorktown on Oct. 19, 1781. This Beetle Bailey cartoon is hardly alone in its inaccuracy. Even the National Park Service says the Yorktown victory was the war's "last major battle," which "secured independence for the United States." The truth is that not only did participants believe the war would continue, but the fighting didn't end until June 25, 1783, and it included battles as significant as Yorktown. The often-used John Trumbull painting of the Yorktown surrender—whose image is used the last Beetle frame—was inaccurate: Cornwallis' second-in-command, Gen. Charles O'Hara, made the actual surrender, and he was on horseback. (Fair use of cartoon for educational purposes)

The bum-bardment of Gibraltar

The French and Spanish besieged the British possession for years, but failed to capture it, even after a 1782 bombardment that used state-of-the-art weapons. The British are in the fortress; the bums belong to their hapless enemies.

The General P—s, or Peace

This British cartoonist in 1783 wasn't thrilled by the Treaty of Paris, which acknowledged the independence of the United States. From left to right, a Brit, Dutchman, Indian who represents the US, Spaniard, and Frenchman—all combatants in the war. The Brit says, "Say what they will, I call this an honourable P—." The American: "I call this a free and Independent P—." The Frenchman: "Jack English, we confess your exceeding good nature, tho' we have wrangled you out of America you freely make P— with us."

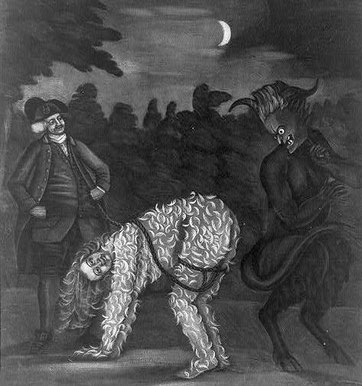

Tarring and feathering

A favorite American rebel tool of intimidation—and torture.

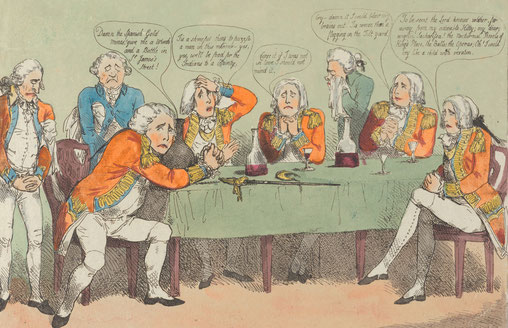

Heroes

Members of the British Coldstream Guard are despondent because they are being sent to fight in America. "We'll be food for the Indians to a certainty," says the second-from-left soldier. Another says, "Damn it, I could blow my brains out." Morale was a major issue on all sides, and desertion was rampant.

State cooks

George III to the left tells the prime minister, Lord North, that "the loss of these fish will ruin us forever"—the fish being the colonies. North assures the king that "I will cook 'em yet."

Marie Antoinette and the Marquis de Lafayette, riding a penis ostrich

This cartoon has nothing to do with the American Revolution after Yorktown—except Lafayette was a leading general at Yorktown, and France helped bankrupt itself by joining the war and contributing millions of livres (a monetary unit) to the rebels. The American Revolution also inspired the French Revolution, which is when this cartoon was published in a political pamphlet. After the American Revolution, Lafayette returned home and led the French National Guard for a couple of years. He was a centrist and supported a constitutional monarchy—and being a centrist in the middle of a revolution means you're road kill. ("There's nothing in the middle of the road but yellow stripes and dead armadillos"—Jim Hightower). Although Marie-Antoinette despised Lafayette, revolutionaries believed he was in cahoots with the royal family and even had an affair with her—thus this cartoon, one of many insinuating a sexual relationship. Lafayette was later imprisoned by radicals and is honored today far more by Americans than by the French.